The Power of Water

How Hydropower Plants Work

When watching a river roll by, it’s hard to imagine the force it’s carrying. If you have ever been white-water rafting, then you’ve felt a small part of the river’s power. White-water rapids are created as a river, carrying a large amount of water downhill, bottlenecks through a narrow passageway. As the river is forced through this opening, its flow quickens. Floods are another example of how much force a tremendous volume of water can have.

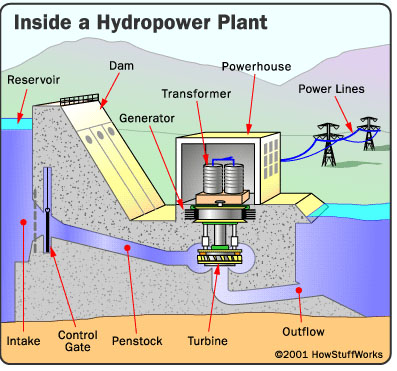

Hydropower plants harness water’s energy and use simple mechanics to convert that energy into electricity. Hydropower plants are actually based on a rather simple concept — water flowing through a dam turns a turbine, which turns a generator.

Here are the basic components of a conventional hydropower plant:

The shaft that connects the turbine and generator

Dam – Most hydropower plants rely on a dam that holds back water, creating a large reservoir. Often, this reservoir is used as a recreational lake, such as Lake Roosevelt at the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State.

Intake – Gates on the dam open and gravity pulls the water through the penstock, a pipeline that leads to the turbine. Water builds up pressure as it flows through this pipe.

Turbine – The water strikes and turns the large blades of a turbine, which is attached to a generator above it by way of a shaft. The most common type of turbine for hydropower plants is the Francis Turbine, which looks like a big disc with curved blades. A turbine can weigh as much as 172 tons and turn at a rate of 90 revolutions per minute (rpm), according to the Foundation for Water & Energy Education (FWEE).

Generators – As the turbine blades turn, so do a series of magnets inside the generator. Giant magnets rotate past copper coils, producing alternating current (AC) by moving electrons. (You’ll learn more about how the generator works later.)

Transformer – The transformer inside the powerhouse takes the AC and converts it to higher-voltage current.

Power lines – Out of every power plant come four wires: the three phases of power being produced simultaneously plus a neutral or ground common to all three. (Read How Power Distribution Grids Work to learn more about power line transmission.)

Outflow – Used water is carried through pipelines, called tailraces, and re-enters the river downstream.

The water in the reservoir is considered stored energy. When the gates open, the water flowing through the penstock becomes kinetic energy because it’s in motion. The amount of electricity that is generated is determined by several factors. Two of those factors are the volume of water flow and the amount of hydraulic head. The head refers to the distance between the water surface and the turbines. As the head and flow increase, so does the electricity generated. The head is usually dependent upon the amount of water in the reservoir.